Read More:

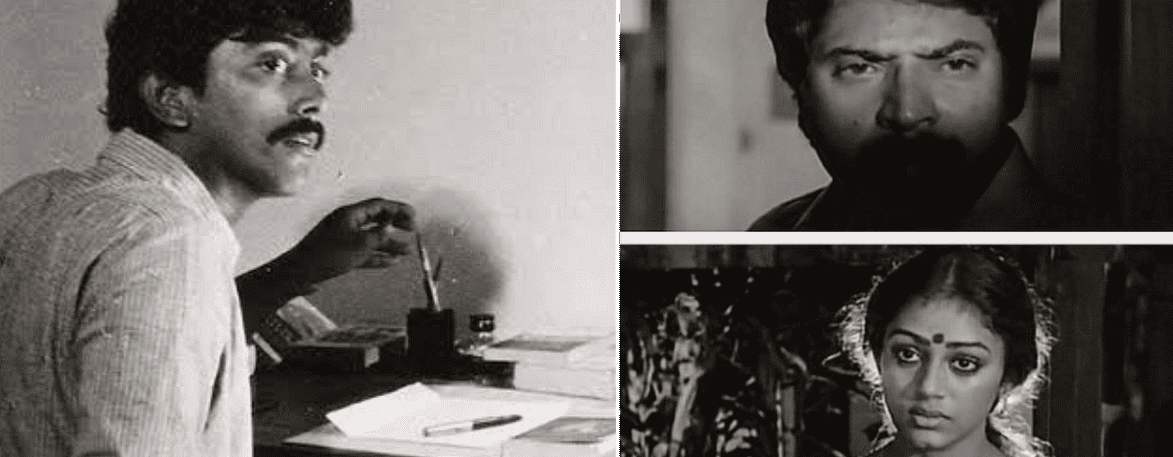

If the protagonist is blanketed in Psychosis, how can a movie narrate his or her story? It is such a humongous task to crack his or her original perspective and do justice to it! The easier way is to let this particular life unfold through the eyes of some other character. This would have been easier if the medium is a novel or a short story. Because the author will have the liberty to describe all the thoughts vividly. If it is for a cinema, then the writer and director will have to adapt a novelistic approach and tweak it into some particular non-linear form that the protagonist’s mind demands. One such stellar work is Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Anantaram, which got released in 1987.

Film buffs usually claim that, before Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp fiction, there weren’t any notable movies that played around with the chronology in the novelistic approach. Even its tagline says it is “three stories about one story”. But 7 years before Pulp Fiction, Anantaram excelled in the circular novelistic approach.

The movie begins, develops, and then ends through Ajayan’s monologue. So even though the word Anantaram means “hereafter”, Adoor sir gave it an additional English title when he sent the subtitled version to all the film festivals, “Monologue”. But this doesn’t mean it entirely relies on the monologues. Adoor sir has used monologues in the right proportions, just enough to initiate the visual storytelling.

Some online articles claim that after his fourth movie, Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s wife who was pregnant with their daughter came home after a routine check-up and mentioned a story she heard from the hospital. Somebody had abandoned an infant in the hospital and eventually, a doctor adopted it. The whole idea of Anataram was born there it seems. Or maybe he was forming bits and pieces of Anantaram in his mind and how his wife narrated it to him became a fortunate stroke of serendipity? Anyway, that incident was later developed as the opening scene of Anantaram, to make it concrete that the root of all Ajayan’s problems began right from this first abandonment itself. Later, in his teens, Ajayan even confides with his step-brother Balu that if he ever finds out who his birth mother is, he would strangle her.

In the first act, we get to know that, in his early teens, Ajayan had a crush on his super senior Latha. But she was in love with somebody else. His pursuit to find someone to mingle with finally enforces more loneliness into his life. In his own words, “I don’t know the reason, but even in my age group, there was no one I could call a true friend. I had nothing to say to them, nor they had anything to offer me either. My only friends were Dr. Uncle with who I went for evening walks and his son Balu, who used to stay with us during vacations.”

As the movie evolves further, we witness that apart from these two friends, all he had was the companionship of the old servants of his step-father. They are the ones who constraint the intellect of little Ajayan to mysticism too which further clogged his thoughts.

Till the mid-point, Ajayan narrates a story about himself in which he begins as an all-rounder. But this over-excellence in every field makes him alienated in his classrooms and gradually as he grows up, in the society too. Nobody likes the way he knows everything. He seems to know way more than what his teachers can teach him. His teachers or his classmates don’t seem like his stern stands and touches of sarcasm unnerve them. In his youth, Ajayan who is a lot more lone than before meets Suma, whom his step-Brother Balu marries. Slowly her presence starts to intimidate him someway. Nothing is overtly explained through dialogues, and visual storytelling is at its best here. Adoor’s recurring cinematographer Mankada Ravi Varma conveyed the duality in Ajayan’s mind through the different shades of light that fall on Ajayan’s face when he witnesses the marriage. Gradually he realizes that her presence is further choking his sense of belongingness.

From mid-point till the end, he restarts the narration from childhood. But this time, he lets us witness the situations which he didn’t mention earlier. But this time, some moments make us wonder whether we should rely on his narrations entirely. Some of them, especially his interactions with the old servants have a tinge of mysticism. Slightly extramundane situations that hook our attention even more. He has fallen for Nalini, but his imagination is fabricating such a woman out of his muddled thoughts about Suma, right? Wait, what if Nalini is not a hallucination? When something confuses the protagonist, the movie beautifully incites the same level of ambiguity in us viewers too. As if the narrator is trying to explain that he also has thought about the reasons for all the confusing psychotic episodes in his life, but he is unable to give a clear cut explanation.

So if the first chapter, the first half of the movie, is letting us peek into the effect. Meanwhile, the second chapter, the second half of the movie, is more like a glimpse into the cause.

In the final scene, he goes back to childhood for the third time. He initiates this with a befitting monologue comprising of 2 sentences. “I am not sure if I have told you the complete story. There may still be things I have forgotten to relate.”

Little Ajayan is on the top of the steps which leads downwards to the banks of the river. He walks down skipping every alternate step and counts aloud. So at first, he says out loud all the odd numbers till 37. He runs to the top again and repeats the same, but this time skips the odd steps. He counts loud till 38 as he reaches the final step. He turns around and looks up, right into our eyes. All the lines on the screen leading to his confused look.

At that moment, when the screen freezes, Ajayan concludes his narration, and we will ask ourselves what will happen in Ajayan’s life hereafter?

The movie gives us no other option, other than fusing both the chapters in our minds. Though the movie concludes on the screen, it will create some tension in us and we will tend to project the fused version in our mind.

Even if you try to figure out the logic, psychosis never lets someone like Ajayan narrate the same story twice. So he narrates both the tales up until the current situation, where all his versions would converge. The plot and the protagonist demanded such a form and structure.

Like the structure of Anantaram, let us circle back to where this article on Anataram began. What do you think would have happened, if the protagonist Ajayan narrates his reliable or unreliable stories in chronological order?

He was institutionalised for 6yrs in a Film Institute, to forget about the 4yrs which an Engg college stole. Inveterate dreamer who dreams to utter Spielberg’s words, “I dream for a living.”